In my overviews of looking around Europe, I noted that lower speed limits were prevalent virtually everywhere I went. Yet, in New Zealand we are still only taking a few hesitant baby steps towards similar environments. There are a lot of benefits of lower speeds for transport and society in general; if you want to look into this further, I urge you have a look at a recent thesis by one of my Masters students, Lisa Williams. But here I’d like to focus particularly on the benefits for active modes like walking and cycling.

-1024x647.jpg)

As you may have seen, last week I proposed to Christchurch City Council that they investigate introducing lower speed limits (ideally 30km/h) in a number of areas that I consider “low hanging fruit”, namely:

- Suburban shopping streets, like Riccarton, Sydenham, Merivale (to go with the new CBD 30k zone)

- Residential areas with existing traffic calming, such as Papanui East, Addington, Edgeware

- Schools that don’t already have school speed zones (over 80 such schools in Chch)

Strangely enough, a lot of the resulting media attention focused on the relationship of lower speeds with cycling (even though they are just one of the beneficiaries). And clearly even a lot of people who cycle don’t quite get how it can help them. A lot of discussion is currently on getting safer cycleways like the planned Major Cycleway Routes around Chch. But even when they’re completed in ~5 years time, that will still only be another 100 km or so of better cycling routes – what about the other 1500+ km of streets around the city?

That’s where lower speed limits can have a more immediate effect on a larger portion of the city. Often we’re talking about local streets that don’t have much traffic anyway, but that remaining traffic there travels faster than desirable. Or we’re talking about busier areas where there is a lot of road user interaction happening (e.g. parking, school kids, shoppers, buses) and it’s a bit harder to concentrate on everything at the same time.

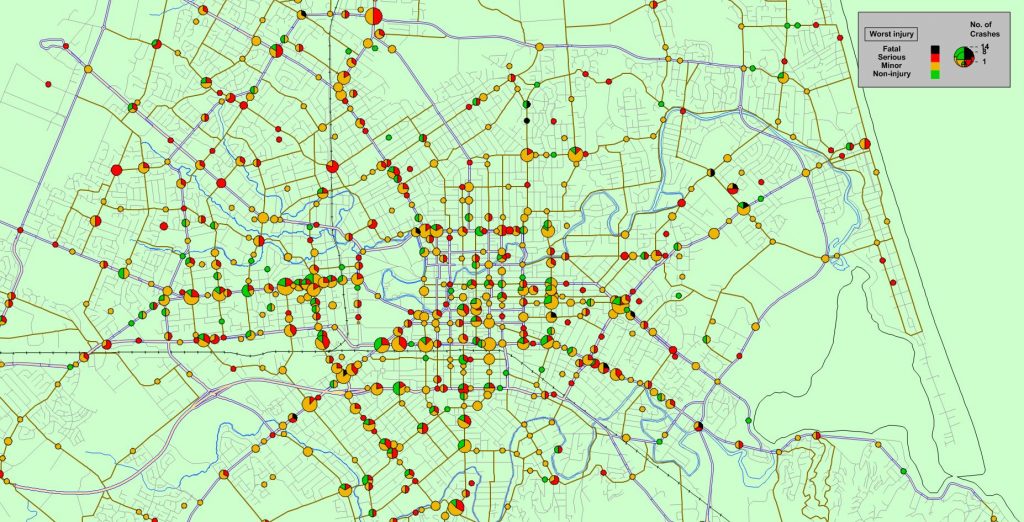

Safety is the biggest motivation for introducing lower speeds. We have a lot of road crashes in New Zealand, relative to the best places in the world, and people walking and cycling seem to bear a large brunt of those in urban areas. While preparing to present to Council, I had a look at how many pedestrian and cycle crashes had occurred in Christchurch since 2010. The figure was staggering – over 1200 injuries over 5½ years, including 18 fatalities and 350 serious injuries. And many of these crashes were clustered in a few key areas around town, especially in suburban shopping areas.

Critics of lower speeds say that the real problems are poor road designs (e.g. no separated cycleways) and poor road user behaviour (e.g. “those bloody cyclists wobbling all over the road”). While there’s no doubt it would be great to see improvements on both fronts, you will never get perfection in either area – we’re human and we have limited transport resources. A “safer system” approach accepts that these failings of both people and the transport system will occur and aims to prevents bad outcomes as a result. Just because you made a mistake shouldn’t result in serious injury or death.

That’s where lower speeds can make a real improvement to both the likelihood and severity of traffic crashes. Internationally the evidence has found very big reductions in crashes following speed management, especially in terms of fatalities or walking/cycling injuries. Locally in Wellington, where 30km/h suburban shopping streets have been introduced in the past five or so years, there has been an 82% reduction in injury crashes. The differences in risks are particularly significant for active modes. Typically the risk of serious injury or fatality halves when going from an impact speed of 50km/h to 40km/h and drops fivefold when going from 50 to 30.

But it’s more than just about safety. Lower speed environments also encourage more people to walk and cycle (due to the calmer environment provided), with all the health and environmental benefits that brings. And it also makes for more pleasant places to live, work and play, resulting in economic benefits from the improved amenity (e.g. higher property values, more local shopping). Other places have already recognised these benefits, such as Hamilton’s Safer Speed Areas in residential suburbs.

A number of other objections are often raised about lower speed limits:

- “Lowering Speed Limits will greatly increase Travel Times” – Maybe a little, but most traffic delay is due to other traffic or occurs at intersections. Reduced travel times might be more important on arterial routes but generally they aren’t affected by lower speed zones. It’s also important to remember that getting from A to B quicker is not the only form of “economic productivity”, so beloved by Government. You are likely to gain more economic benefits from crash savings of reduced speeds, health benefits of encouraging more active transport, retail benefits from encouraging passing trade to linger, and property value benefits due to more liveable neighbourhoods. Basically it’s about trading a little mobility for vastly improved amenity.

- “The average traffic speed is already well below the speed limit” – So reinforce that with an enforceable speed limit! It seems rather incongruous to design a lower speed environment (e.g. the planned Riccarton bus priority route) but not match the speed limit. Having a lower speed limit also sends a clear encouraging message to those who wish to walk or cycle.

- “The public don’t want reduced speeds” – Not surprisingly there is always a number of people who don’t want to be slowed down. A majority of the Automobile Assn’s members for example apparently aren’t keen on 40km/h speed limits. But the key is to identify whose opinion is more important. Those using a local neighbourhood area as a rat-run short-cut might not want reduced speeds. But those living and walking/riding there probably do, and on local streets their views should get more weight.

- “Lower speed limits alone won’t change traffic speeds” – If you have concerns that a street environment encourages speed, then add some additional traffic management features to get the speeds down a bit more. That’s why I focused initially on areas where the typical travel speeds are already low. However it’s not true that speed limit signs on their own have no effect. The evidence is very consistent that, for every 10 km/h speed limit reduction, typically you observe a 2‐3 km/h reduction in mean speeds. That might not seem much, but again the research has found that every 1% speed reduction typically results in a 2% reduction in crashes and a 4% reduction in fatalities.

- “We’re not like Europe…” – This always seems like a strange objection – we’re not human? We still get injured at high speeds just the same as Europeans. But places in Europe that introduced lower speeds also had the same kinds of objections when they first introduced them (until the positive results were hard to ignore). And the rest of the world seems to be following suit too; you are more likely to find speed limits below 50km/h in Australia and North America too.

Lower speeds are not a panacea for all sins. But, at a time when our road toll decline is stagnating, the one key tool that we haven’t picked up from overseas yet is to introduce lower speeds more widely on our roads.

Do you think lower speed limits would make for a better cycling environment?

Have there been any figures published in major media for any of NZ’s cities that indicate how much extra time a typical drive would take if limit dropped from 50 to 30? It would increase some, however as noted above perhaps not that much as there’s so many other things causing delays. Maybe if people knew how much they’d be more willing to consider a trial change? Show figures like 5km trip driven typically takes xx mins of which xx minutes was stationary, xx was at 0-15kph, xx at 15-30kph, xxmins at 30-50kph (& xx at 50-65kph).

I know at peak times I cycle my 8km route in virtually identical time to car, or sometimes faster than car. At other times of day I’m a bit slower than car. Based on that & that my peak speed is about 35kph I’m guessing 30kph limit at peak times may make little to no difference? But saying that I can filter at lights whereas cars can’t so perhaps it’s an unfair conclusion & maybe big(ger) queues would form. Anyone got any data?

The increased travel times argument is a red herring foisted upon the public by the technocrat traffic industry. Most neighbourhoods in NZ have been wrecked by the presupposition that traffic speeds (and travel times) equate economic activity. The best way to think about this is the trips that aren’t counted. What is missing from the equation are all the trips that are foregone or forced into cars to make the most mundane daily activities: kids getting to school, the trip to the dairy, the town centre down the street, etc. All of these trips don’t count.

Slowing speeds in neighbourhoods enable these trips. In addition to the safety and amenity value there is a legitimate economic rationale for allowing people to make short trips without the requirement of a car.

Instead of arguing that slower traffic speeds are insignificant (they are), I think it is better to disregard the overall premise that traffic speed on urban streets and neighbourhoods has ecomomic value.

Great post LennyBoy.

There was an amusing article on TV ONE’s Seven Sharp a while back with a reporter moaning about the proposed new 30km/h limit in the Chch CBD. To illustrate the difference in time, she drove a route through town at both 50k and 30k… except that the 30k drive took less time! As I say above, it’s mostly other traffic and intersection that delay you, not the speed limit. See http://tvnz.co.nz/seven-sharp/drive-slow-video-5666200

I think it will not only benefit cyclists and pedestrians but also make a street more attractive (for living, relaxing or shopping). A 30kph limit in most suburban streets would also allow kids to play on the streets again. I would like to see most or all non high capacity roads restricted to 30 kph. We also lack car-free streets in the CBD.

Keep up your great work Glen!

I have always wondered why speeds weren’t lower than 50kmph on suburban roads. I live down a cul-de-sac which is very narrow and am always shocked at the high speeds other residents choose to travel down it at (given how short and narrow it is).

Do you think there’s any chance some of these speed changes will ever eventuate?

I had a great response from Council to my presentation and they are planning to look into it further (including looking at other local examples to date, like Wgtn and Hamilton). At a national level, things are also sloooowwwwly getting better at allowing for lower speed limits, through the development of a draft Speed Management Guide (https://www.pikb.co.nz/additional-resources/) and planned changes to the Setting of Speed Limits Rule. So yes, it will happen, just a question of when.