Having previously covered the innocuous legal question of what exactly constitutes a bike, we’ll now turn our attention to where exactly you can ride your bike (and some of the implications of that). Before we get too far into that, it’s helpful to understand two key definitions in NZ legislation:

- A “road” has a very broad definition in land transport rules here. As originally defined in the Land Transport Act 1998, a road includes “a street; a motorway; a beach; a place to which the public have access, whether as of right or not; all bridges, culverts, ferries, and fords forming part of a road or street or motorway; and all sites at which vehicles may be weighed for the purposes of this Act or any other enactment.” Thinking about that definition seems to include an awful lot of places – is your local park a “road”? What about a public library? {Apparently it can be: a person who once rode their motorcycle onto an escalator in the old Christchurch Central Library was charged with a driving offence!} NZ Transport Agency have tried to help clarify just what a “road” means, although it may still leave a few questions to be tested in court one day. The definition is deliberately quite broad so that road rules can control behaviour of drivers and vehicles in places other than your garden-variety street (e.g. you could probably be charged with reckless driving for hooning around people in your car in the middle of a busy sports-field) – it doesn’t however mean that you have free access to actually drive (or ride) in all of these places (e.g. you still can’t generally drive on a lawn or garden forming part of a “road”).

-1024x455.jpg)

- A “roadway” meanwhile is defined as “that portion of the road used or reasonably usable for the time being for vehicular traffic in general.” In simple terms, the distinction usually boils down to: the “roadway” is the bit between the kerbs and the “road” is the bigger bit between the fence-lines (property boundaries). Many rules about intersections, turning, passing and parking refer to behaviours that occur on roadways, not roads.

Taking on board those definitions, here are a few interesting rules relating to where you can cycle (or not):

- As I mentioned above, just because something is considered part of a “road” doesn’t automatically mean you can ride there. For example, use of an ordinary footpath (or grass berm) is prohibited on a bike unless you are delivering material like newspapers {I have heard of people carrying some printed material with them when biking, in case they get stopped on a footpath by a cop…}. Despite the common mis-perception, children are not allowed to bike on footpaths either (that rule applies in Australia), unless their bike is so small that it is classed as a “wheeled recreational device” instead. In practice, the Police tend to turn a blind eye, especially if kids are riding slowly and carefully.

-

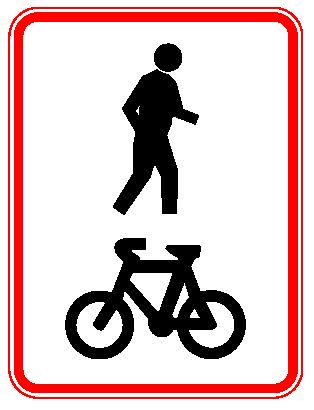

Shared Path sign It is only on signed/marked shared paths (i.e. for pedestrians and cyclists) that you’re allowed to ride freely off-road; even there all path users still have an obligation to use it in a “careful and considerate manner”, e.g. you can’t create a hazard for other users or unduly impede their passage. Shared paths should be denoted by either signage or markings that show both cycle and pedestrian symbols (Christchurch City Council is even now going to the effort to record shared paths in their Traffic Bylaw as well; not entirely sure if that is necessary). Although not common practice here in Christchurch, in some parts of the country you may encounter signs that indicate separate parts of a path for those walking and cycling, or that indicate a priority of one group over the other (although everyone still has an obligation not to impede others, regardless of any priority).

- One of the current headaches in NZ is determining what category a separated cycleway falls into (i.e. separated by a kerb, posts, or something similarly physical) – are they part of the roadway or are they behind the roadway like a footpath? This has some implications for situations like side-roads; if you are considered on the roadway then (like ordinary motor traffic) you have priority over side-road traffic, but if you are considered off it then (like a person on a footpath) you would have to give way to side-road traffic. Some legal interpretations suggest that the latter is the current case in NZ law, which is not really intended for many new cycleways, so there is some work going on behind the scenes to tidy up and clarify this legislation. In the meantime, for now, don’t necessarily assume that you have right of way on separated cycleways at side-roads (but you do have right of way when crossing driveways).

- The mandatory bike helmet rule in NZ applies to “roads” (not roadways) so, yes, that does technically mean you need to be wearing it in the middle of Hagley Park or along the beach (whether a Police officer would bother ticketing you there is another matter…). I’ve seen a few people who seem to be trying to avoid the problem of not having a helmet by riding on the footpath – unfortunately for them they’re now technically up for two offences; footpath riding and helmet-less riding…

-

No cycling allowed here Motorways are the common exception to general access to roads for bikes; the Government Roading Powers Act 1989 generally prohibits bikes from operating there (although intriguingly it does allow the possibility that their operation can be approved on certain sections of motorway). Other places that might prohibit cycling (e.g. certain “expressways”) are usually indicated by signs, but that restriction does need to be backed up with an accompanying bylaw by the relevant roading agency. {Interestingly, despite having “No Cycling” signs along QEII Drive and Anzac Drive, I’m not aware of any actual current legal restriction for on-road cycling along this route, as NZTA didn’t carry over the bylaw when they took it over as a State Highway from Chch CC…}

- So, what if there is an on-road cycle lane or off-road cycle path – do you have to use them? The short answer is no, you are completely free to determine where it is best to ride for yourself (e.g. to turn right, get past pinchpoints, or to avoid pedestrians). Bear in mind of course that you still have an obligation not to unduly impede other traffic (and we all know that some motorists get very antsy when some riders don’t use “their cycleway”…). One exception is with previously-mentioned prohibited roads like motorways, where you are likely to be directed onto a pathway at the start that you have to use. Conversely, motorists are not allowed to drive in cycle lanes, unless they are crossing them or avoiding an obstruction, and even then they have to give way to any bikes there first.

That in a nutshell sets out your rights in regards to where you can bike – sometimes it’s where motor traffic is, sometimes it’s where pedestrians are, and sometimes it’s in your own dedicated space. In the next legal issues segment we’ll look at what kind of equipment and other things you can (or must) have with your bike. As always, I also welcome feedback on other legal things you’d like to know about cycling.

Do you have any legal questions about cycling in NZ? Contact us!

-1200x533.jpg)

Some years ago, when living in Auckland, a police officer visited my daughter’s then-primary school and explicitly told the kids to ride on the footpath, it’s safer (suburb was Greenlane, so there was some truth in that). So they don’t just turn a blind eye: some actively recommend it.

Question: what about speeds on shared paths? I assume that the posted speed limit applies on roadways, but many shared paths don’t have posted speed limits, yet anything much about 20 seems inappropriate when pedestrians are around.

There are no posted speed limits, and how would you know if you’re going over any specified number? Speedos are not mandatory fitments.

However there’ll be some classic woolly phrase like “unsafe speed” of “dangerous speed” where its totally up to the discretion of the officer.

The Setting Speed Limits Rule is virtually silent on speed limits other than on roads (although as you have seen here, the definition of “road” is quite broad). It would seem that if a shared path was parallel to a roadway (i.e. part of the same “road”) then the prevailing speed limit there would apply.

As mentioned above, any users of a shared path must act always in a “careful and considerate manner” as well; the Rule includes a specific obligation for users of wheeled devices to “not operate the cycle or device at a speed that constitutes a hazard to other persons using the path.” Needless to say, this still is a judgement call and will depend a bit on the situation, e.g. 20km/h when you squeeze past another path user might be way too much, whereas 30km/h when you are more than a metre clear might be perfectly fine.

Yep. Keyword: Judgement. The more Rules we have, the less we are left to our own judgement and the poorer our judgement becomes. Studies have shown a clear correlation between reductions in road rules and an increase in both social responsibility and road safety. If you look at ‘traffic’ behaviour in a typical Spanish town square, for example, where the ‘road’ is open to pedestrians, cyclists and motor vehicles, everyone naturally assumes the role of road user, exercises a lot more judgement moving about and is generally a lot safer than they are in a typical ‘controlled’ town centre environment. As the renowned Dutch traffic engineer Hans Monderman remarked, “The greater the number of prescriptions, the more people’s sense of personal responsibility dwindles”. His work around the concept of Shared Space is fascinating.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shared_space

Is a cycle classed as a vehicle,if not what rights do they have to be on a road.

Hi Trevor, go to the first link at the top of this article, which explains that a cycle is a vehicle (but not a motor vehicle). The short answer is yes, cycles have the right to be on roads.